|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

scientific files |

|

|

| |

|

The French tsunami warning centre will be located at Bruyères-le-Châtel |

By 2012, France will have built its tsunami warning centre for the Western Mediterranean and North-eastern Atlantic. It will be based at the CEA/DAM-Ile de France Centre and managed by the teams of the Environmental Assessment and Monitoring Department (DASE in French). By 2012, France will have built its tsunami warning centre for the Western Mediterranean and North-eastern Atlantic. It will be based at the CEA/DAM-Ile de France Centre and managed by the teams of the Environmental Assessment and Monitoring Department (DASE in French).

For the DASE, 10 March 2009 will definitively mark the beginning of a new scientific adventure. Indeed, on this date, the General Administrator received a common letter from the Ministries of Interior and for the Environment, indicating that they entrusted the CEA with the responsibility of designing and then operating a tsunami warning centre, by equipping it with the appropriate means. The future centre will be established at Bruyères-le-Châtel and will cover the monitoring of the Western Mediterranean and North-eastern Atlantic (Spain and Portugal). This choice, which recognizes the unique competence of the CEA in the field of tsunamis and warning systems, is the result of very many discussions which have taken place over the last few years.

The history starts with the catastrophic tsunami which occurred on 26 December 2004 in the Indian Ocean, raising the awareness of the international community to the risk of tsunamis. Very quickly, that is, from the beginning of 2005, UNESCO received a mandate to coordinate the setting up of warning systems in the three basins which were not yet monitored: the Indian Ocean, the Caribbean, the Mediterranean and North-eastern Atlantic. The fourth basin, corresponding to the Pacific, was already equipped with a warning system set up in the 1960s in response to the devastating tsunamis related to earthquakes in Chile (1960) and Alaska (1964). Besides, the CEA developed its expertise within the framework of the Pacific warning system, as much in the understanding of the phenomenon (in particular, by digital simulation) as in the operational warning systems themselves.

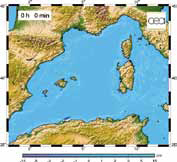

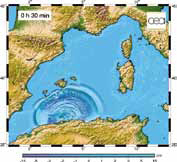

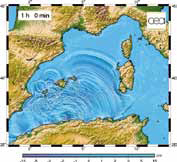

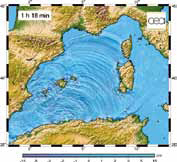

Tsunamis can occur in the Mediterranean. Here, the snapshots show digital simulations (carried out by the DASE) of the propagation of the tsunami of 21 May 2003 following the Boumerdes earthquake. Sea state at the time of the earthquake, on arrival of wave at the Balearic Islands 30 minutes later, one hour after the earthquake, and, finally, on arrival along the French coasts, 68 minutes later. Tsunamis can occur in the Mediterranean. Here, the snapshots show digital simulations (carried out by the DASE) of the propagation of the tsunami of 21 May 2003 following the Boumerdes earthquake. Sea state at the time of the earthquake, on arrival of wave at the Balearic Islands 30 minutes later, one hour after the earthquake, and, finally, on arrival along the French coasts, 68 minutes later.

In 2006, the French Ministry of Interior asked the CEA to study the possibility of setting up a tsunami warning centre for the Western Mediterranean and the North-eastern Atlantic, in order to respond to the requests of UNESCO. A new stage began in November 2007, when France decided to give a wider regional dimension to this project: the warning centre would have to alert not only the French civil protection authorities, but also the services concerned in countries bordering the Western Mediterranean. In February 2008, the CEA gave a positive reply, subject to having the adequate human and financial resources.

Over the last few months, the DASE teams have been actively preparing the setting up of the future warning centre. Objective: to be operational in mid 2012, thus respecting the recommendations of UNESCO.

15 minutes for a warning 15 minutes for a warning

The objective of the Tsunami warning centre for the Western Mediterranean and North-eastern Atlantic is to provide, in less than 15 minutes, the first information concerning potentially tsunamigenic earthquakes. In view of the fact that most tsunamis are induced by earthquakes, this short interval is related to the very short lead time between the onset of an earthquake and the arrival of a possible tsunami. The orders of magnitude of the arrival time of tsunamis in this zone are estimated at 10 to 15 minutes along the coasts close to the epicentre, and from 10 minutes up to a little more than 1 hour along the French coasts, according to the location of the seismic event.

This constraint implies two special challenges:

-

to develop a very fast, powerful and robust system for processing the geophysical data in real time, so, in a few minutes, it is possible to characterize an earthquake and its tsunamigenic potential;

- to set up and maintain standby duty personnel, i.e. experts present at the DIF centre around the clock, to treat the events of interest.

This challenge will be met while working in partnership with the SHOM (Hydrographic and Oceanographic Service of the French Navy)

and the INSU (National Institute for Sciences of the Universe of CNRS), which will contribute certain data to the warning centre.

Tsunamis cause considerable damage in ports. The photograph shows scattered debris near the port of Aonae, on the island of Okushiri in Japan, following the tsunami of 12 July 1993. Tsunamis cause considerable damage in ports. The photograph shows scattered debris near the port of Aonae, on the island of Okushiri in Japan, following the tsunami of 12 July 1993.

In the event of a tsunami warning, messages will be sent to the French authorities responsible for civil protection, which will take steps on whether or not to start evacuation of the coast (primarily beaches and ports).

At the international level, messages of information will be transmitted to the other national and international tsunami centres in the area, as well as the participants named by the Member States. These organizations or services ensuring a round-the-clock stand-by will have the role of alerting their own national civil protection service, which, in its turn, will take the responsibility of whether or not to start an evacuation of their coastal zones.

Very quickly, if the tide-gauge data confirm the tsunami, other messages will be disseminated at the national and international level.

Seismometers, tide-gauges

and tsunameters Seismometers, tide-gauges

and tsunameters

From the technical point of view, several types of sensors are necessary to detect the formation of tsunamis.

The most common type of sensor are seismometers, which record the seismic waves. To ensure effective seismological monitoring in real time, high bandwidth communication links will be installed as of mid 2011 to exchange data with the Spanish, Portuguese, Italian and German seismological centres. The DASE will also install satellite links on certain seismological stations of the INSU.

The centre will also have access to tide-gauge data. These sensors, which record the tsunami waves along the coasts, will make it possible to confirm or rule out the arrival of a tsunami. The French tide-gauges are set up and maintained by the SHOM with which the DASE maintains very close relations. These data will be transmitted to the Bruyères-le-Châtel warning centre by various means of telecommunication. In the event of an alert, as soon as a tide-gauge records the tsunami propagation, its time of arrival, amplitude and period will be transmitted to the authorities and the other national and regional centres.

Finally, tsunameters will also provide their harvest of data. Like the tide-gauges, these sensors record the tsunami wave, but in offshore areas and far away from the coast.

In the long term, when the system is complete, it will comprise more than 60 seismometers, 50 tide-gauges and 10 tsunameters, which will transmit all their recordings in real time to the warning centre.

The contribution of data

processing The contribution of data

processing

The seismologist on stand-by duty will have a control screen displaying the real-time data from tens of seismometers, tide-gauges and tsunameters. Concretely, the seismologist will have to pick out a tsunami among this avalanche of data, and to do so in just a few minutes. To enable very rapid operation, the centre will make use of automatic programmes, which will detect any signal potentially related to a tsunami.

In the future Tsunami warning centre, experts will be on duty around the clock. In the future Tsunami warning centre, experts will be on duty around the clock.

This software will be developed by the end of 2011, and will be implemented on the servers used to equip the centre. Scenarios will be modelled as a preliminary step to build up a data base of potential events. In practice, the person on stand-by duty will validate the results of the automatic software and check the location of the seismic event, determining whether it is located at sea or very near to the coast, as well as its magnitude and depth.

Operational data bases (seismological and tsunami observations) will provide additional information to assess whether or not a tsunami could be induced. Lastly, automatic modelling software will allow us to calculate the time of arrival of the tsunami and estimate the water surface elevation offshore.

The warning messages will only be issued when the expert on stand-by duty has validated all this information.

|

|

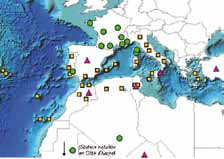

| Seismic stations belonging to: |

France (13) France (13) |

CTBTO (6) CTBTO (6) |

Others (31) Others (31) |

| |

Network of seismic stations for the Western Mediterranean and North-eastern Atlantic. Network of seismic stations for the Western Mediterranean and North-eastern Atlantic.

|

|

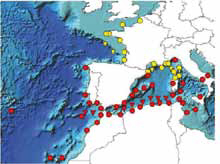

| Sea-level measurement points 85) : |

| Tide-gauges |

tsunameters |

|

|

|

France (31) |

|

|

Others (54) |

| |

|

|

Programmed network for sea-level measurement in the Western Mediterranean and North-eastern Atlantic. Programmed network for sea-level measurement in the Western Mediterranean and North-eastern Atlantic.

Tsunamis in the Western Mediterranean, Spain, Morocco and Portugal: fiction or reality? Tsunamis in the Western Mediterranean, Spain, Morocco and Portugal: fiction or reality?

In the Western Mediterranean, the most recent benchmark tsunami occurred just 18 months before the enormous tsunami in the Indian Ocean. On 21 May 2003, an earthquake of magnitude 6.8, which seriously affected the area of Boumerdes (50 km east of Algiers, death toll of more than 6000), triggered a tsunami observed throughout the Western Mediterranean. The geological context here cannot be compared with the long subduction zones of the Pacific or Indian Oceans. The regional seismicity is due to slow convergence between the tectonic plates of Africa and Eurasia, which has persisted for approximately 40 million years. However, the characteristics of the geological structures and tectonic settings concerned are still poorly known, which makes it more complex to identify the active faults.

This 18 th century engraving shows the tsunami which devastated Lisbon on 1 November 1755, following the earthquake that occurred on the same day with a magnitude estimated at 8.5. This 18 th century engraving shows the tsunami which devastated Lisbon on 1 November 1755, following the earthquake that occurred on the same day with a magnitude estimated at 8.5.

The tsunami of 2003 crossed the Western Mediterranean in less than 1 hour 20 minutes, initially affecting the Balearic Islands, where more than one hundred boats were damaged, or even sunk, and where several local backflows and floods were noted. It was recorded on a score of tide-gauges installed in Spanish, French and Italian ports. Later research revealed an impact extending as far as some small ports of the Riviera, where a rapid fall of sea level was observed. This was associated with currents and eddies as well as the draining out of harbours, which locally hindered small craft navigation, and which continued for several hours. Little information is available on the Algerian side: either the tsunami could not be observed or it was very weak. This event pointed out that even a moderate impact (in terms of flooding) is accompanied by a considerable economic cost, a tendency that can only be exacerbated with the increasing vulnerability of the tourist coasts.

In the Western Mediterranean, earthquakes of magnitude exceeding 7 are possible (earthquakes of 1954 and 1980 in Algeria), and some of them will be tsunamigenic. In 1856, a tsunami was triggered by an earthquake of magnitude 7.2 in the area of Djijel (East Algeria). The effects of this event are still unknown. Earthquakes in the Ligurian Sea (off the Riviera ) are known to have generated tsunamis, as observed in February 1887, when several coastal sites (Cannes and Antibes) were locally flooded following an earthquake of magnitude greater than 6. Again, in this case, there is little information concerning other affected sites.

Tide-gauge installed by the Hydrographic and Oceanographic Service of the French Navy in the port of Ajaccio. Tide-gauge installed by the Hydrographic and Oceanographic Service of the French Navy in the port of Ajaccio.

On quite another scale, the benchmark event for the area is naturally the Lisbon earthquake of 1 November 1755 (magnitude estimated at 8.5). The subsequent tsunami flooded many parts of the Portuguese and Spanish coasts, thus adding to the number of victims from the earthquake. The impact of this catastrophe was, at the same time, human, scientific and philosophical. Today, this earthquake is very poorly understood, because there are no known regional tectonic structures that appear adequate to explain the probable magnitude. For such an event, distant coasts experienced sea-level variations sometimes in excess of several metres. Certain observations exist for the Antilles, as at certain sites on the southern coasts of Ireland and Great Britain. On the North-east coast of America, as well as on the French Atlantic coast, we lack any eyewitness accounts of movements of the sea at that time.

For all these areas and events, this brief overview reminds us that the risk of a tsunami, even if relatively low, is indeed a reality in the Mediterranean region. To obtain a better understanding of these phenomena, many studies remain to be carried out as regards historical observations, as well as on the geodynamic characteristics and vulnerability of coastal areas.

|

|

|